How did Arabic writing become an art?

Arabic calligraphy has been developed since the advent of Islam in the seventh century. The writing of the Qur’an played a central role: indeed, copies of the sacred text can only be made in a handwriting that is always neat, unlike that used in administrative documents. It is thus above all in the Koranic manuscripts that appears the “beautiful writing” of the Arabic language. Later on, it also adorned works of a secular nature, art objects and monuments, thus becoming one of the characteristic features of Islamic art.

The oldest preserved manuscripts of the Qur’an are dated to the late seventh and eighth centuries. They are copied in a script called hijazi, with letters that are often slender and slanted, characterized by a simple layout. From the ninth century onwards, Arabic writing aimed at aesthetic perfection with a new calligraphic style known as “kufic” (after the city of Kufa, in Iraq), or “angular”. It is characterized by sharp edges between the horizontal part (base) and the vertical part (shaft) of the letters. In order to respect the layout, the calligrapher modulates the characters, lengthening, stretching or tightening them. Some manuscript pages have only a few lines of kufic writing, which explains why some prestigious Korans are made up of several dozen volumes.

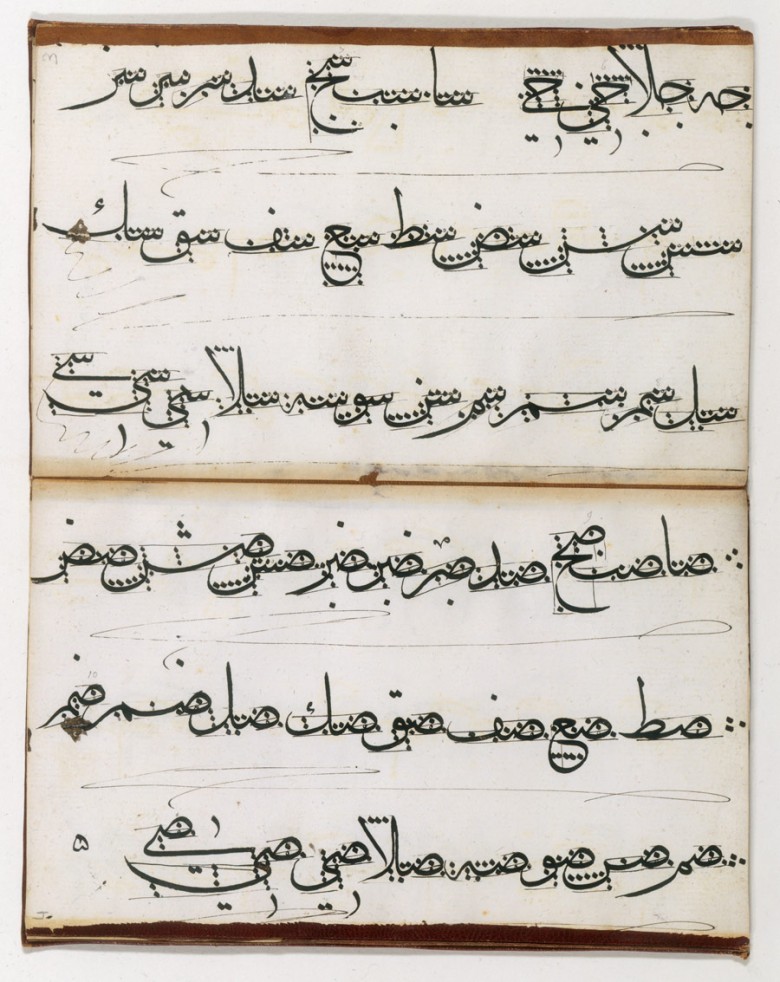

In the tenth century, paper supplanted parchment, allowing for an increasingly massive production of books in the Arab world. Other calligraphic styles developed, such as the so-called “cursive” scripts, with a more flexible and rounded line. Very varied, they break with the graphic unity of kufic. The naskhi then spread in the Muslim East, the maghribi in the Maghreb and in Muslim Spain.

Maghribi calligraphy: page from the Qur’an calligraphied by Muhammad al-Qandousi, 19th century, Rabat, Royal Library of Morocco. Marocimages/IMA

Arabic calligraphy became a major art form throughout the Islamic world as it was codified by prestigious masters such as Ibn Muqla and Ibn al-Bawwab. These two calligraphers, who lived at the court of Baghdad in the tenth and eleventh centuries, established a system of rules theorizing a “well-proportioned writing”, making calligraphy a rigorous discipline. The calligrapher traces with the calamus – the bevelled reed used as a writing instrument – a reference circle starting from the alif, the first letter of the alphabet. All the other letters of the alphabet must be inscribed in this circle. The proportions of each letter are then determined by a measuring point. The shape of the letters forces calligraphers to do a lot of research using these circles and reference points. The writing becomes perfectly legible.

Calligraphy models by Muhammad al-Hashimi, 1688-89: each letter is measured by means of squares made with the tip of the calamus. BNF

In Baghdad in the 13th century, Yaqut al-Mustasimi perfected naskhi and defined six canonical calligraphic styles: naskhi, muhaqqaq, thuluth, riqa, rayhani and tawqi. These styles were brilliantly cultivated throughout the Muslim East from the 14th century onwards. The Persians and Ottomans, who adopted the Arabic alphabet to write their own language, i.e. Persian and Turkish, gave a new impulse to these different styles. They also invented new ones, such as nastaliq.

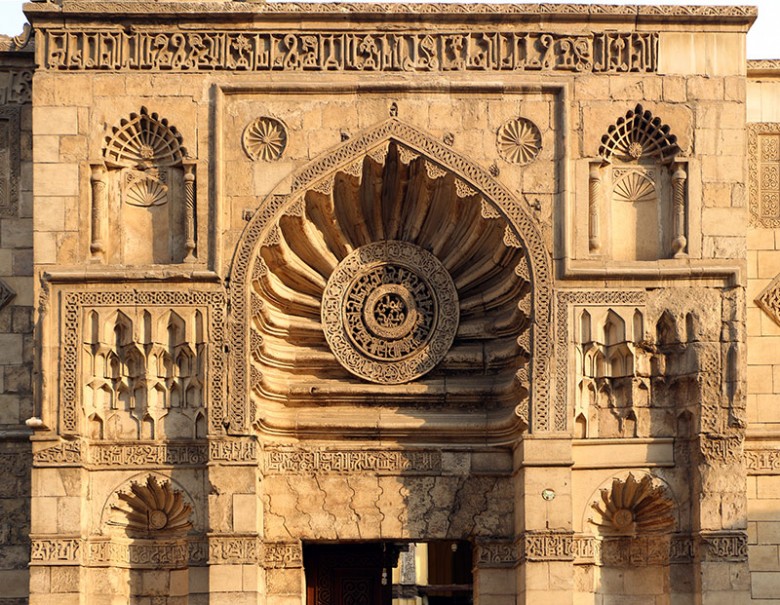

With its rules and styles, Arabic calligraphy was therefore the subject of very strict and rigorous teaching. Apart from manuscripts, inscriptions also appear in specific compositions, often in a sacred context. They magnify architecture, ceramics, but also the arts of metal, glass or textiles. Calligraphic friezes appear on these different supports, embellished with geometric or vegetal ornaments. In addition to its utilitarian function, calligraphy assumes a decorative role that sometimes emphasizes a strong symbolic dimension. Even today, contemporary calligraphers continue to develop this art. Writing styles such as naskhi and maghribi are still in use.